Abstract

Rachel’s agreement with Leah in Genesis 30:14–24 to exchange sex with Jacob for mandrakes discovered by Leah’s son, Reuben, constitutes an exchange of sex for fertility drugs. The story is rooted in an ancient fertility myth in which mandrakes are understood to possess physical and chemical properties that enhance fertility. This article examines this exchange of sex for drugs in Genesis 30:14–24, the nature of mandrakes and the origin of the fertility myth, including the origin of the legend of the shrieking mandrake which is misattributed to Josephus, and examines the myth’s reception history, including apologetic devices employed by later biblical and extra-biblical authors to disguise the fertility myth, its efficacy, and the willingness of the biblical characters to participate in it.

Introduction

The legends of the fertility-enhancing properties of mandrakes and their fatal shrieking are known from some of humanity’s greatest literature. William Shakespeare (1564–1616) refers to mandrakes on six occasions in five separate plays—twice with regard to their renowned fertility properties,[1] twice with regard to the shrieking the mandrakes are said to make when extracted from the earth,[2] and twice describing mandrakes as charms to be worn.[3] Niccolò Machiavelli penned a 1518 satirical comedy titled Mandragola, in which the legendary reputation of mandrakes as a fertility aid is the centerpiece of a sophisticated plot to sleep with another man’s wife. The second line of English poet John Donne’s famous Song (ca. 1590) reads “get with child a mandrake root.” And of course, J. K. Rowling’s second book, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (1998), includes a classic scene where the Hogwarts students repot shrieking baby mandrakes with Professor Pomona Sprout while defending themselves from death with earmuffs.[4]

The literary tropes depicting mandrakes as useful for coaxing another into sex and the production of offspring trace back to the Bible. Rachel’s arrangement with Leah in Gen. 30:14–24 to trade an evening of sex with Jacob for mandrakes discovered by Leah’s son, Reuben, constitutes an exchange of sex for drugs, specifically, supposed fertility enhancers. The story is rooted in an ancient fertility myth in which mandrakes are understood to possess both physical and chemical properties that enhance fertility.

The mandrake narrative is actually the first of two consecutive stories preserving ancient fertility myths, the second being the story in Gen. 30:37–39 of Jacob’s surprisingly successful use of the now-debunked breeding technique of visual eugenics called “maternal impression” as a method of engineering desired physical traits in offspring. Maternal impression proposes that the child of a sexual union comes to possess the physical characteristics of whatever the mother was viewing or envisioning in her mind during intercourse, with both positive and deleterious effects.[5] According to the Bible, this is why Jacob’s manipulation of the poplar tree rods—creating black and white streaks in them—and his placing of them in front of the troughs where the ovine herds ate and bred resulted in striped and speckled offspring, despite the fact that Laban had removed all of the genetically striped, spotted, and speckled animals from his herds (Gen. 30:35).[6]

This article examines the origins of the former mandrake fertility myth in Gen. 30, its presence in the biblical narrative, and the apologetic techniques used by post-biblical authors to distance the Bible and biblical characters from this fertility legend.

Mandrakes as Ancient Medicine

Ancient medicine largely revolved around concoctions of naturally occurring plants and chemicals combined with elements of magic and religion. This is due to the fact that ancient healing practices were understood as a combination of petitioning deities associated with healing and drugs or chemicals that could change the state of consciousness of the patient. The rise of shamanism represents an early combination of mind-altering drugs with spiritual entreaty and maneuvering, which Ioan Couliano has argued evolved to incorporate developments in various religious traditions.[7] By the mid-5th C. BCE, Greek physicians had come to be associated with Asclepius, the god of healing, who became the divine patron of the medical profession as healers had done earlier with Ningishzida in Mesopotamian mythology. Basil Gildersleeve argues that the cult of Aphrodite Ambologera (Ἀμβολογήρα), who had a statue on the acropolis at Sparta by this epithet and is mentioned in Pausanias,[8] is based on the identification of the goddess with the mandrake.[9]

Origins of the Mandrake Fertility Myth

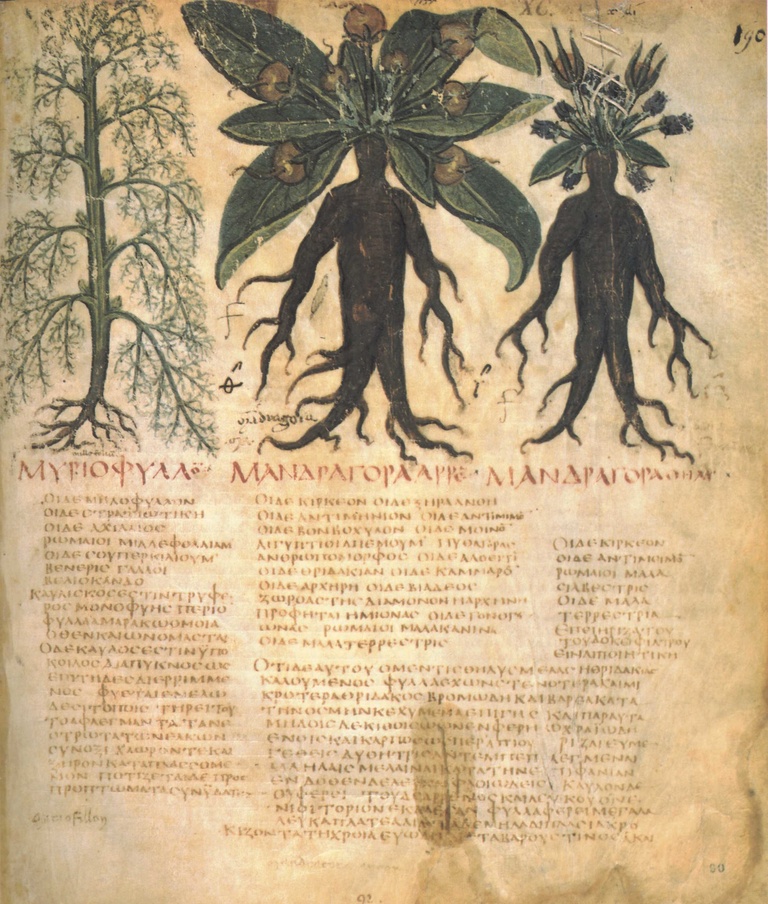

One of the naturally occurring plants commonly used as a drug in antiquity is the Mandragora officinarum, commonly called the mandrake. Mandrakes belong to the family of plants called Solanaceae, taking its name from the Latin verb sōlor, meaning “to soothe, comfort.” Solanaceae are a family of flowering plants that includes a number of important agricultural crops including Solanum (potato, tomato, eggplant), Physalis philadelphica (tomatillo), Capsicum (chili pepper, bell pepper), Petunia, Datura, (Cape gooseberry flower), Mandragora (mandrake), Nicotiana (tobacco), Atropa belladonna (deadly nightshade), Lycium barbarum (wolfberry), and Physalis peruviana. Mandrakes contain hyoscine (also known as scopolamine), which possesses both hallucinogenic and narcotic properties. Today hyoscine is used to treat motion sickness and nausea and in the 1900s began to be used as an anesthetic.

Mandrakes were identified at least four millennia ago as possessing chemicals that could alter the mind, and which were thought to increase fertility, likely due to their soporific and inhibition-reducing effects. However, the post-consumption experiences were often so mentally and physically unpleasant to the body that mandrakes garnered a reputation as dangerous medicine and were not a popular repeat-use drug.

These medicinal properties associated with mandrakes are well attested among the classical authors.[10] The Hippocratic Corpus (460–370 BCE) prescribes boiling green (fresh) mandrake root, soaking it in wine, and applying it as a poultice to inflamed areas of skin.[11] Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE) describes the problems that mandrakes can cause for bears,[12] and mentions mandragora as a substance that can be used to make artificial wine.[13] He offers a lengthy description of the plant as “curative of defluxions of the eyes and pains in those organs,” while stating that its narcotic effect causes it to be “given, too, for injuries inflicted by serpents, and before incisions or punctures are made in the body, in order to ensure insensibility to the pain.”[14]

The first century CE Greek physician, pharmacologist, and botanist Pedanius Dioscorides (40–90 CE) discusses mandragora (mandrake) at length in his De Materia Medica. First, he states that “Mandagoras has a root that seems to be a maker of love medicines.” After describing the plant and the various ways it is prepared for ingestion, he discusses the soporific and anesthetic properties of the plant stating, “They use a winecupful of it for those who cannot sleep, or are seriously injured, and whom they wish to anesthetize to cut or cauterize…they do not notice the pain because they are overcome with dead sleep.” Dioscorides also states that the mandrake “expels the menstrual flow and is an abortifacient” and cures a litany of additional ailments including reducing the size of tumors, goiters, and scars.[15]

For the most part, the classical sources understood mandrakes as a soporific employed sparingly to bring about sleep. Demosthenes (384–322 BCE) references mandragora as a soporific drug in his (disputed) Fourth Philippic,[16] and Xenophon (431–354 BCE) cites Socrates as saying, “for wine does of a truth moisten the soul and lull our griefs to sleep just as the mandragora does with men.”[17] Aristotle (384–322 BCE) lists mandragora along with poppies as a narcotic that causes “head heaviness.”[18] In one analogy, Plato (428–348 BCE) mentions mandragora as a substance used to drug a ship captain.[19] Aulus Cornelius Celsus (25 BCE–50 CE) suggests placing mandrake apples under one’s pillow to induce sleep,[20] and mentions mandragora as part of an ingestible soporific remedy, but one that is “worse for the stomach.”[21] Plutarch (46–120 CE) lists mandrakes along with opium among the narcotic drugs that “work violently” to put men to sleep,[22] and suggests that mandrakes growing next to grapevines yield grapes that produce wine that “makes the sleep of those that drink it more refreshing.”[23]

Mandrakes as Fertility Enhancer

It is this sleep-inducing property that likely led to the “fertility enhancing” myth, as drowsiness led to decreased inhibitions during potential sexual encounters. The early-3rd C. CE author Athenaeus mentions that a playwright named Alexis penned a play titled Woman Drugged with Mandrake.[24]

The fertility-enhancing reputation of mandrake consumption was enhanced by the bifurcated, anthropomorphic shape of the mandrake root. Because the roots themselves look like rudimentary human figures, many in antiquity came to identify the mandrake with reproduction, perhaps following a similar folk reproductive principle to the maternal impression myth that drove the story of the reproduction of Jacob’s sheep in Gen. 30:37–39. Several pre-classical and ancient Near Eastern literary and artistic examples also depict mandrakes as possessing fertility-enhancing properties.

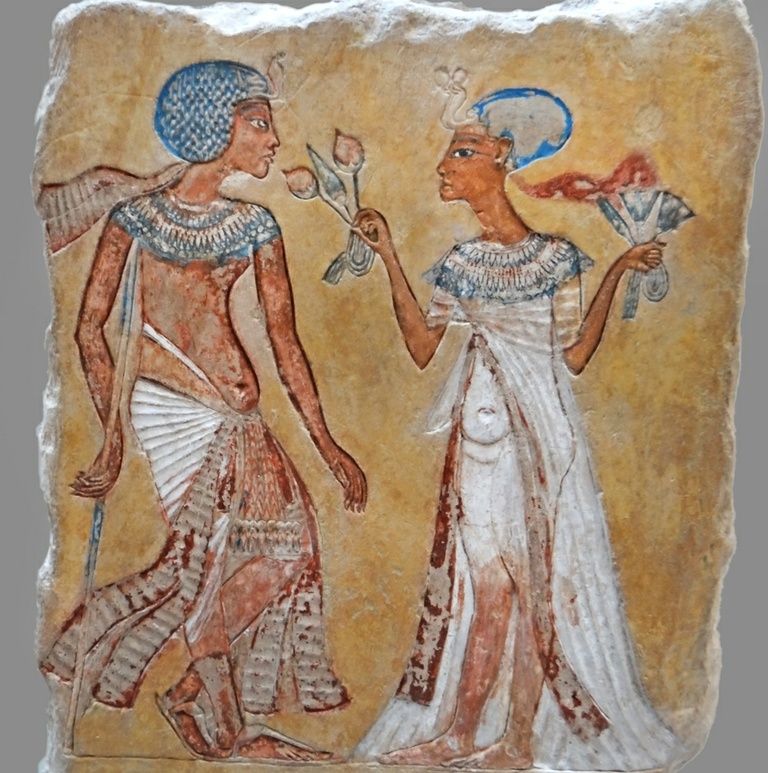

Evidence linking mandrakes with fertility and the (re)generation of life dates back at least to the 18th Dynasty of Egypt (1550–1350 BCE).[25] Mark D. Merlin has described a ritual healing scene depicted on a colored limestone dating to the late 18th Dynasty, on which the short-lived King Smenkhkare (r. 1335–1334 BCE), is depicted as leaning on a crutch while being offered two mandrake fruits and a bud of Nymphaea nouchali by his consort, Meritaten (eldest daughter of Akhenaten), who also holds more N. nouchali flowers in her left hand. The panel suggests that Meritaten is offering the mandrakes to her husband in an effort to prolong his life or to produce children before he died. The fact that the couple produced no known children supports this interpretation.[26]

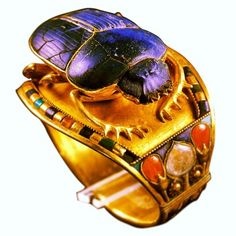

We also find mandrakes on a gold bangle featuring an openwork scarab encrusted with lapis lazuli representing King Tutankhamun.[27] Two identical botanical arrangements appear on each side of the bracelet, each consisting of a mandrake fruit flanked by two poppy buds, with gold marguerites filling the spaces between the stems below. The yellow and green colors of the mandrakes are painted from the rear of the translucent quartz inlay. In the same way that the ancient Egyptians adopted the beetle (Scarabaeus sacer) as a symbol of the sun god, due both to its supposed autogenic traits and its everlasting survival skills in the harshest desert climes, so too did the Egyptians depict the mandrake as a life-giving symbol of fertility on much of their royal iconography.

Mandrakes, however, appear to have developed a popular fertility myth despite attempts to limit knowledge of the “magical” effects of the plant to religious circles in ancient Egypt. Merlin cites William A. Emboden, Jr., who argues:

“the most significant forms of evidence that seem to link the sacred blue lily and mandrake, along with the opium poppy, Papaver somniferum, to the priestly caste are the papyri, ‘.... books of the dead, books of ritual magic, and related pictorial evidence—which were never meant to be seen by the public—present those same plants that are the vehicles to ecstasy’ (Emboden 1989).”[28]

It is possible that belief in the fertility-enhancing powers of the mandrake could have been transmitted from Egypt to Canaan, where it was then incorporated into early Israelite mythology. Egypt’s contact with Jerusalem at the time of the Amarna Letters demonstrates that the Egyptian royal court was in communication with the elite in Canaanite Jerusalem, providing a line of communication that could have transmitted sacred and healing knowledge.[29] We’ve already seen that mandrakes were an established part of the Egyptian priestly caste in the time of Tutankhamen (r. 1332–1323 BCE), had already been employed in the treatment of infertility, and were believed to aid in the transition into the afterlife—that is, the regeneration of life—as evidenced in Egyptian tomb art. Thus, mandrakes provide several chronological and archaeological links that allow for the transmission of the mythology about the restorative and life-giving powers of the mandrakes from Egypt to Canaan.

The Myth of the Shrieking Mandrake

I must offer a corrective note regarding the origin of the myth of the shrieking mandrake. I noted earlier Shakespeare’s reference to the shrieking mandrake tradition in Romeo and Juliet Act IV, Scene 3: “And shrieks like mandrakes torn out of the earth, That living mortals, hearing them, run mad.” Shakespeare’s reference suggests that the tradition dates back to antiquity, or so it appears at first.

Despite considering them absurd, Theophrastus (371–287 BCE) recounts many folk traditions involving the harvesting of medicinal plants (considering them “absurd”—ἄτοπον), offering with regard to cutting the mandrake root, “It is said that one should draw three circles around it with a sword, and cut it facing west; at the cutting of the second piece one should dance around the plant and say as much as possible about sexual intercourse.”[30] Pliny also mentions the ritual of “tracing three circles round it with a sword” and “turn towards the west and dig it up.”[31] Interestingly, neither Theophrastus nor Pliny mention the mandrake screaming.

Another detailed account of this extraction myth comes from Flavius Josephus, who offers a comically macabre solution for harvesting a mandrake while avoiding the lethal damage deriving from its root. Josephus does not call the plant a mandrake by name, offering a local appellation instead. William Whiston’s translation of Jewish War 7.180–185 reads as follows:

180 “There is a certain place called Baaras (Βαάρας), which produces a root (ῥίζαν) of the same name with itself;

181 its color is like to that of flame, and towards the evening it sends out a certain ray like lightning: it is not easily taken by such as would do it (καὶ βουλομένοις λαβεῖν αὐτὴν οὐκ ἔστιν εὐχείρωτος), but recedes from their hands (ἀλλ᾽ ὑποφεύγει), nor will yield itself to be taken quietly (καὶ οὐ πρότερον ἵσταται), until either the urine of a woman, or her menstrual blood, be poured upon it;

182 nay, even then it is certain death (πρόδηλός ἐστι θάνατος) to those that touch it, unless anyone take and hang the root itself down from his hand, and so carry it away.

183 It may also be taken another way, without danger, which is this: they dig a trench quite round about it, till the hidden part of the root be very small,

184 they then tie a dog to it, and when the dog tries hard to follow him that tied him, this root is easily plucked up, but the dog dies immediately (θνήσκει δ᾽ εὐθὺς ὁ κύων), as it were instead of the man that would take the plant away; nor after this need anyone be afraid of taking it into their hands (φόβος γὰρ οὐδεὶς τοῖς μετὰ ταῦτα λαμβάνουσιν).

185 Yet, after all this pains in getting, it is only valuable on account of one virtue it hath, that if it be only brought to sick persons, it quickly drives away those called Demons (δαιμόνια), which are no other than the spirits of the wicked, that enter into men that are alive, and kill them, unless they can obtain some help against them.”[32]

We must note a few things about Josephus’s account. First, while Josephus does not call the Baaras “mandrakes” (mandragora) by name—a term he uses in Ant. 1:307—we find that Joseph preserves the legend of the deadly, evasive, and agile plant pulled from the earth that comes to be associated with mandrakes.[33] Note also that Josephus does not speak of the fertility benefits of the Baaras root, but says rather that its one virtue is that “it quickly drives away those called Demons (δαιμόνια)” that otherwise “enter into men that are alive, and kill them, unless they can obtain some help against them.” The general attribution of disease to demon or spirit possession was a common belief in the first C. CE. The fact that Josephus is recommending this root for “casting out daemons,” which is his expression for the general healing of all disease ailing the body, supports the classical authors’ description of the mandrake as a potent medicine for just about every ailment.

Most interestingly, we must note that Josephus never specifically mentions that it is a shriek or scream that kills the dog—only that “the dog dies immediately” (θνήσκει δ᾽ εὐθὺς ὁ κύων) from some temporary phenomenon, as the human can then carry the mandrake “without being afraid of taking it [into their hands]” (φόβος γὰρ οὐδεὶς τοῖς μετὰ ταῦτα λαμβάνουσιν) once the mandrake root is pulled from the ground by the (now) deceased dog.[34] At no time does Josephus warn that the one tying the dog should stand at a great distance before calling the dog. Jewish War 7.184 reads: κἀκείνου τῷ δήσαντι συνακολουθεῖν ὁρμήσαντος ἡ μὲν ἀνασπᾶται ῥᾳδίως (“and when that one has urged the bound one to follow along, the [root] is easily drawn up”). Josephus offers no suggested distance to stand from the mandrake, suggesting that the cause of the dog’s death is not likely to be sonic, but instead based on physical contact with or immediate proximity to the root.

Furthermore, nowhere in Josephus’s legend of the mandrake and the dog is there any word that describes anything of an acoustic nature.[35] Whiston’s choice of words in his 1737 translation of Jewish War 7.181 appears to be the result of his own reading of the shriek tradition back into his translation of Josephus. Note that Whiston translates ἀλλ᾽ ὑποφεύγει καὶ οὐ πρότερον ἵσταται as “but recedes from their hands, nor will yield itself to be taken quietly,” while a better translation would be “but it flees below and does not stand upright until...” Whiston’s use of the word “quietly” may have been a conscious or subconscious allusion to the medieval screaming mandrake legend retrojected back into Josephus’s first century text.

It appears that the legend of the mandrake’s shriek does not appear until the 12th C. Bestiary by Anglo-Norman French poet Philippe de Thaon (or Thaun), which offers 23 lines on the mandrake (following a lengthy description of elephants, who were often associated with them), giving us the earliest explicit literary reference to the mandrake’s shriek:

‘The man who will gather it—must dig about it

Softly and gently—so that he does not touch it.

Let him take a chained dog—let it be tied to it,

Which is right ravenous—and three days fasted.

Let bread be shown it—from far let it be called;

The dog will pull it—the root will break,

And will utter a shriek—the dog will fall dead

Through the shriek which it heard—such force has this plant

That no one can hear it—but at once he must die.

And if the man hear it—on the spot will he die;

Therefore he must stop—his ears and take care

That he hear not the cry—lest he die just the same

As the dog will do—if it hear its cry.’[36]

This is followed by a 13th C. reference to a shrieking mandrake from The Bestiary of Guillaume le Clerc, a Norman-French manuscript dating from 1210–11:

“They say when it is plucked,

That it moans and shrieks and cries,

And if any one hear its cry,

Dead he will be and come to grief.”[37]

Thus, it appears that the legend of the shrieking mandrake did not arise until the anthropomorphic nature of the mandrake root became increasingly central to the legend of the plant. The shock that killed the dog referenced by Josephus’s tale later came attributed to the shriek made by the anthropomorphic root, not some demon or disease as in Josephus's account. Shakespeare made the mandrake’s scream famous, and Whiston appears to have read this tradition back into his translation of Josephus’s Jewish War suggestively using the term “quietly” in 7.181.

Regardless of the nature of the lethal blow, the legend of the deadly mandrake extraction is the result of the increased market value of the plant that resulted from its medicinal worth as a fertility enhancer. Additionally, Anthony Preus states, “The mystique surrounding the pharmakon does help preserve the monopoly of the root digger or drug seller: if gathering the plant requires a complicated ritual to avoid coming to harm, the layman is the more likely to keep away from it.”[38] Once the otherwise common weed was believed to have therapeutic and monetary value, landowners likely sought to deter trespassers from harvesting mandrakes growing wildly in their fields by concocting the myth that the anthropomorphic root would shriek a fatal scream when pulled from the ground.

Mandrakes in the Hebrew Bible

Mandrakes are described in the Hebrew Bible as דוּדָאִים (dudaʾim). The Samaritan Pentateuch spells the word as דודים (dudim), without the aleph. The word appears to be etymologically related to, and perhaps derived from, the Hebrew word דּוֹד (dōd), or “beloved,” likely due to the mandrake’s reputation of possessing properties that enhance virility, fertility, and fecundity throughout antiquity. This Semitic understanding persists into the rise of Arabic, where mandrakes are called اللفاح نبات (al-lifah nabaʾat) and described as “love fruits” resulting in the nickname the “devil’s apples.”

The association of mandrakes with seduction and lovemaking within the Hebrew tradition is exhibited in Song of Songs 7:13 (HB 7:14), where mandrakes are mentioned in the plural with a prefixed definite article (הַדּוּדָאִים) in the obvious context of certain “choice fruits” related to seduction: הַדּוּדָאִים נָתְנוּ–רֵיחַ וְעַל–פְּתָחֵינוּ כָּל–מְגָדִים חֲדָשִׁים גַּם–יְשָׁנִים דּוֹדִי צָפַנְתִּי לָךְ (“The mandrakes give forth fragrance, and over our doors are all choice fruits, new as well as old, my beloved, which I have reserved for you.”) Note the obvious play on the words for “mandrakes” (דּוּדָאִים) and “my beloved” (דּוֹדִי), which likely strengthened the etymological roots of the fertility myth by associating mandrakes with one’s romantic partner.[39]

Michael Zohary argues, “Dudaim in Genesis 30:14–15 can certainly not be Mandragora, which has never grown in Mesopotamia, where Jacob, Leah and Rachel lived.”[40] Of course, this view assumes both the historicity of the patriarchs and of the mandrake episode in Gen. 30, and neglects the anachronisms involved when later authors, compilers, and redactors write stories using contemporary cultural knowledge from the Mediterranean, where mandrakes do grow, when writing about the patriarchs. There is no reason to reject the identification of דודאים as mandrakes simply because mandrakes aren’t attested in Mesopotamia, especially when the knowledge of the myth was known to later redactors, who could have incorporated the myth despite its anachronistic or geographic implausibility.

Mandrakes in Genesis 30

The text of Gen. 30:14–16 describes an exchange of mandrakes (and its powers of fertility) for sexual access to Jacob—an exchange of drugs for sex—and Gen. 30:17–24 details the children resulting from this exchange.

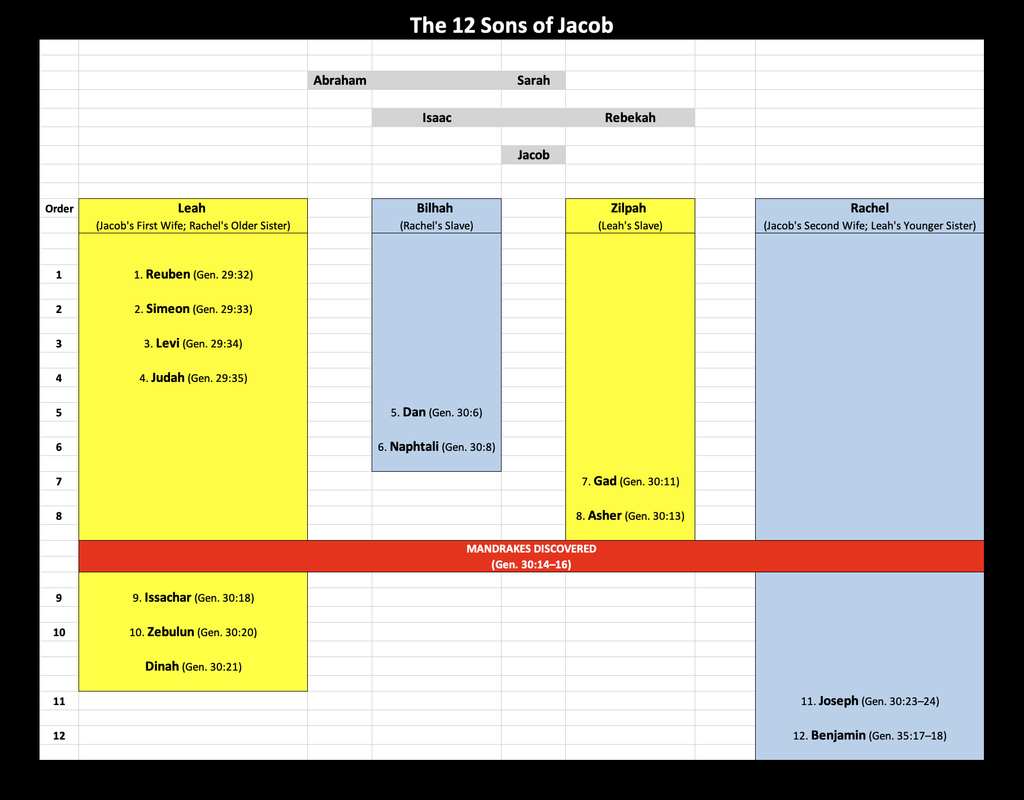

Prior to the reference to the mandrakes in Gen. 30, Leah is said to have given birth to Reuben (29:32), Simeon (29:33), Levi (29:34), and Judah (29:35), after which the author clearly states regarding Leah in Gen. 29:35: וַתַּעֲמֹד מִלֶּדֶת (“and she ceased bearing”). Interestingly, the text implies that this was to be the original culmination of Leah’s childbearing. This fact is emphasized by the repetition of this fact in Gen. 30:9: וַתֵּרֶא לֵאָה כִּי עָמְדָה מִלֶּדֶת (“And when Leah saw that she had ceased bearing [children]…”). Leah had become so distraught by her eventual barrenness that she emulated her desperate sister Rachel, who offered Jacob her servant Bilhah as a surrogate, using her own maid, Zilpah. Both servants bore additional children for Jacob; Rachel’s servant, Bilhah, bore Dan and Naftali, while Leah’s servant, Zilpah, bore Gad and Asher.

It is at this point—after Leah is said to have stopped bearing, Rachel is still barren, and both sisters have exhausted their servants as surrogate child bearers—that we encounter the fertility myth of the mandrakes. Genesis 30:14–16 reads:

וַיֵּלֶךְ רְאוּבֵן בִּימֵי קְצִיר–חִטִּים וַיִּמְצָא דוּדָאִים בַּשָּׂדֶה וַיָּבֵא אֹתָם אֶל–לֵאָה אִמּוֹ וַתֹּאמֶר רָחֵל אֶל–לֵאָה תְּנִי–נָא לִי מִדּוּדָאֵי בְּנֵךְ

וַתֹּאמֶר לָהּ הַמְעַט קַחְתֵּךְ אֶת–אִישִׁי וְלָקַחַת גַּם אֶת–דּוּדָאֵי בְּנִי וַתֹּאמֶר רָחֵל לָכֵן יִשְׁכַּב עִמָּךְ הַלַּיְלָה תַּחַת דּוּדָאֵי בְנֵךְ

וַיָּבֹא יַעֲקֹב מִן–הַשָּׂדֶה בָּעֶרֶב וַתֵּצֵא לֵאָה לִקְרָאתוֹ וַתֹּאמֶר אֵלַי תָּבוֹא כִּי שָׂכֹר שְׂכַרְתִּיךָ בְּדוּדָאֵי בְּנִי וַיִּשְׁכַּב עִמָּהּ בַּלַּיְלָה הוּא

Reuben went in the days of wheat harvest and found mandrakes in the field, and brought them to his mother Leah. Then Rachel said to Leah, “Please give me some of your son’s mandrakes.”

But she said to her, “Is it a small matter that you have taken away my husband? Would you take away my son’s mandrakes also?” Rachel said, “Then he may lie with you tonight for your son’s mandrakes.”

When Jacob came from the field in the evening, Leah went out to meet him, and said, “You must come in to me; for I have indeed hired you with my son’s mandrakes.” So he lay with her that night.

There are several interesting points to this exchange that highlight the potency of the mandrakes. Note first that because the mandrakes were first in Leah’s possession, the very next verses, Gen. 30:17–20, describe her as bearing two additional sons and a daughter, even after “she had ceased bearing sons”:

וַיִּשְׁמַע אֱלֹהִים אֶל–לֵאָה וַתַּהַר וַתֵּלֶד לְיַעֲקֹב בֵּן חֲמִישִׁי

וַתֹּאמֶר לֵאָה נָתַן אֱלֹהִים שְׂכָרִי אֲשֶׁר–נָתַתִּי שִׁפְחָתִי לְאִישִׁי וַתִּקְרָא שְׁמוֹ יִשָּׂשכָר

וַתַּהַר עוֹד לֵאָה וַתֵּלֶד בֵּן–שִׁשִּׁי לְיַעֲקֹב

וַתֹּאמֶר לֵאָה זְבָדַנִי אֱלֹהִים אֹתִי זֵבֶד טוֹב הַפַּעַם יִזְבְּלֵנִי אִישִׁי כִּי–יָלַדְתִּי לוֹ שִׁשָּׁה בָנִים וַתִּקְרָא אֶת–שְׁמוֹ זְבֻלוּן

וְאַחַר יָלְדָה בַּת וַתִּקְרָא אֶת–שְׁמָהּ דִּינָה

And God heard Leah, and she conceived and bore Jacob a fifth son.

And Leah said, “God has given me my hire (שְׂכָרִי), because I gave my maid to my husband”; so she named him Issachar (יִשָּׂשכָר).

And Leah conceived again, and she bore Jacob a sixth son.

Then Leah said, “God has endowed me with a good dowry; now my husband will honor me, because I have borne him six sons”; so she named him Zebulun.

Afterward, she bore a daughter, and named her Dinah.

Genesis 30 never explicitly states that Leah ate the mandrakes, but the text can be interpreted as implying that Leah benefitted from her proximity to or consumption of at least some of the mandrakes, since Rachel asked her only to share “from the mandrakes” (מִדּוּדָאֵי), implying that Rachel only partook of “some” of the plant and/or its fruits, leaving open the possibility that Leah also had access to some of them. However, consumption of the mandrake fruits is not necessary for the efficacy of the mandrakes in the story, as mere possession of the mandrakes (וַיָּבֵא אֹתָם אֶל–לֵאָה אִמּוֹ, “And he [Reuben] brought them to his mother Leah”) was apparently enough to induce renewed fertility. The fact that Leah immediately became pregnant by Jacob and bore two additional sons—Issachar and Zebulon—following coming into possession of the mandrakes, even after Gen. 30:9 states that Leah had עָמְדָה מִלֶּדֶת (“ceased bearing [children]”), was not lost on later interpreters.

Ed Cook sees another possible wordplay that would have been recognizable to Hebrew readers and hearers of this story: “Rachel may get the dudaim (mandrakes), but Leah gets the dodim (love)”, which resulted in three more children for Leah.[41]

Genesis 30:18 requires attention because it preserves a later interpolation intended to disguise this rather obvious case of a child resulting from the acquisition of Jacob’s sexual rights in exchange for drugs. Genesis 30:16 explicitly sets up the etymology of the name Issachar when it records Leah as saying to Jacob: כִּי שָׂכֹר שְׂכַרְתִּיךָ בְּדוּדָאֵי בְּנִי (“for I have indeed hired you (שָׂכֹר שְׂכַרְתִּיךָ) with my son’s mandrakes”). However, because it appeared to later readers that Rachel had sold sexual rights to Jacob in exchange for fertility drugs (mandrakes), Gunkel and others have correctly suggested that this second part of the etymological explanation in Gen. 30:18—the addition of the text אֲשֶׁר–נָתַתִּי שִׁפְחָתִי לְאִישִׁי (“because I gave my maid to my husband”)—following the introduction of the original etymology of Issachar’s name, “God has given me my hire (נָתַן אֱלֹהִים שְׂכָרִי),” is a latter interpolation.[42]

The addition of the reference to the maid is an obvious gloss for several reasons. First, Issachar was borne by Leah, not her maid Zilpah, who bore only Gad and Asher. Thus, Leah’s giving Zilpah to Jacob to bear children is meaningless with respect to Issachar as Zilpah had nothing to do with his birth. Second, שָׂכֹר שְׂכַרְתִּיךָ is expressly used in the initial brokering of the sex exchange deal in Gen. 30:16 in conjunction with the mandrakes, not with Zilpah: אֵלַי תָּבוֹא כִּי שָׂכֹר שְׂכַרְתִּיךָ בְּדוּדָאֵי בְּנִי (“You must come in to me; for I have indeed hired you with my son’s mandrakes”). Furthermore, at no place in the inserted etymology—אֲשֶׁר–נָתַתִּי שִׁפְחָתִי לְאִישִׁי (“because I gave my maid to my husband”)—is there any alliterative or etymological similarity to the name Issachar. While שָׂכֹר שְׂכַרְתִּיךָ (“I have indeed hired you”) sounds like the etymological origin of the name Issachar (יִשָּׂשכָר), there is no similar-sounding word in אֲשֶׁר–נָתַתִּי שִׁפְחָתִי לְאִישִׁי (“because I gave my maid to my husband”). Therefore, we must understand the misplaced reference to Leah’s giving her maid to her husband as a later gloss deliberately designed to obscure the fact that Leah “hired” Jacob for sex from Rachel using fertility drugs, namely mandrakes, and to divert attention away from the role that the mandrakes played in Leah’s fertility.

Genesis 30:22–24 then completes the story by recounting the miraculous conception and birth of Rachel’s first child, which also immediately follows her taking possession of the mandrakes.

וַיִּזְכֹּר אֱלֹהִים אֶת–רָחֵל וַיִּשְׁמַע אֵלֶיהָ אֱלֹהִים וַיִּפְתַּח אֶת–רַחְמָהּ

וַתַּהַר וַתֵּלֶד בֵּן וַתֹּאמֶר אָסַף אֱלֹהִים אֶת–חֶרְפָּתִי

וַתִּקְרָא אֶת–שְׁמוֹ יוֹסֵף לֵאמֹר יֹסֵף יְהוָה לִי בֵּן אַחֵר

Then God remembered Rachel, and God heard her and opened her womb.

She conceived and bore a son, and said, “God has taken away my reproach”;

so she named him Joseph, saying, “May YHWH add to me another son!”[43]

We shall explore several apologetic explanations attempting to occlude the fact that Rachel only got pregnant and successfully bore children after coming into possession of mandrakes shortly. Needless to say, the fact that the text explicitly states, “And God remembered Rachel” (וַיִּזְכֹּר אֱלֹהִים אֶת–רָחֵל) “and heard her” (וַיִּשְׁמַע אֵלֶיהָ) “and opened her womb” (וַיִּפְתַּח אֶת–רַחְמָהּ), only after Rachel came into possession of the mandrakes was not missed by later Jewish interpreters.

Masking the Mandrakes: Reception History of the Mandrake Myth

The Testament of Issachar, written about 150 BCE, provides additional evidence that the phrase אֲשֶׁר–נָתַתִּי שִׁפְחָתִי לְאִישִׁי (“because I gave my maid to my husband”) in Gen. 30:18 is a later gloss into the text. Testament of Issachar 1:3 makes abundantly clear: ἐγὼ ἐτέχθην πέμπτος υἱὸς τῷ Ἰακὼβ ἐν μισθῷ τῶν μανδραγόρων (“I was born the fifth son to Jacob, by way of hire of the mandrakes”). Verse 8 continues: ἡ δὲ εἶπεν Ἰδού ἔστω σοι Ἰακὼβ τὴν νύκτα ταύτην ἀντὶ τῶν μανδραγόρων τοῦ υἱοῦ σου (“And she [Rachel] said: Look, you will have Jacob this night instead of your son’s mandrakes”). Verses 14–15 detail the nature of the exchange:

καὶ εἶπε Ῥαχήλ Λάβε ἕνα μανδραγόραν καὶ ἀντὶ τοῦ ἑνὸς ἐκμισθῶ σοι αὐτὸν ἐν μιᾷ νυκτί

καὶ ἔγνω Ἰακὼβ τὴν Λείαν καὶ συλλαβοῦσά με ἔτεκε καὶ διὰ τὸν μισθὸν ἐκλήθη ἸσαχάρAnd Rachel said: “Choose one mandrake, and in place of this one I will let him out for hire to you for one night.

And Jacob knew Leah, and she conceived and bore me; and because of the wage I was called Issachar.

Note first that T. Iss. portrays Issachar as acknowledging that his name is derived from the fact that, “I was born the fifth son to Jacob, by way of hire for the mandrakes,” with no reference whatsoever to the gloss אֲשֶׁר–נָתַתִּי שִׁפְחָתִי לְאִישִׁי (“because I gave my maid to my husband”) found in Gen. 30:18. Testament of Issachar 15 reiterates this notion explicitly: διὰ τὸν μισθὸν ἐκλήθη Ἰσαχάρ (“because of the wage I was called Issachar”). Thus, T. Iss. reinforces my claim that the reference to Zilpah was a later apologetic gloss attempting to remedy the original story’s portrayal that Jacob was “hired” by Leah in exchange for the fertility-enhancing mandrakes.

The dating of the gloss is problematic as the lack of the presence of the gloss in T. Iss. suggests that it was added after the 2nd C. BCE. However, since the gloss is present in the LXX (~250 BCE) and the Samaritan Pentateuch, it might suggest that the gloss was added earlier, and that the T. Iss. was created from a separate manuscript tradition that did not include the gloss.[44]

The Testament of Issachar alters the canonical story slightly by portraying Rachel stealing the mandrakes from Reuben in 1:4. Thus, in T. Iss., Rachel is negotiating to retain stolen mandrakes rather than to acquire desired mandrakes. Rachel’s reasoning for not wanting to return the stolen mandrakes in T. Iss. 1:6 is worthy of note: εἶπε δὲ Ῥαχήλ Οὐ δώσω αὐτά σοι ὅτι ἔσονταί μοι ἀντὶ τέκνων (“And Rachel said, “I will not give them to you, because they will be mine in place of children”).[45] This translation of the latter half of this verse is peculiar, because the preposition ἀντὶ followed by the genitive plural τέκνων (“children”) is typically translated as “instead of” or “in place of,” which would result in Rachel keeping the mandrakes in the place of the children she does not have. However, as H. C. Kee points out, ἀντὶ can also be translated as “for,” meaning in this context “for means of acquiring” children, supporting the idea that Rachel wanted to keep the mandrakes for the purpose of using them to produce children.[46]

While T. Iss. provides evidence that the phrase אֲשֶׁר–נָתַתִּי שִׁפְחָתִי לְאִישִׁי (“because I gave my maid to my husband”) is a gloss in MT Gen. 30:18 because it is missing from T. Iss., its absence required T. Iss. to provide an alternate apologetic explanation for the presence and efficacy of the mandrake fertility myth. Testament of Issachar 2 provides such an alternative explanation to clarify the Rachel’s covetous actions regarding the mandrakes:

1. Τότε ὤφθη τῷ Ἰακὼβ ἄγγελος κυρίου λέγων ὅτι δύο τέκνα Ῥαχὴλ τέξεται, ὅτι διέπτυσε συνουσίαν ἀνδρὸς καὶ ἐξελέξατο ἐγκράτειαν.

2. καὶ εἰ μὴ Λεία ἡ μήτηρ μου ἀντὶ συνουσίας ἀπέδω τὰ δύο μῆλα, ὀκτὼ υἱοὺς εἶχε τεκεῖν· διὰ τοῦτο ἓξ ἔτεκε, τοὺς δὲ δύο Ῥαχὴλ, ὅτι ἐν τοῖς μανδραγόροις ἐπεσκέψατο αὐτὴν κύριος.

3. εἶδε γὰρ ὅτι διὰ τέκνα ἤθελε συνεῖναι τῷ Ἰακώβ, καὶ οὐ διὰ φιληδονίαν.

4. προσθεῖσα γὰρ καὶ τῇ ἐπαύριον ἀπέδοτο τὸν Ἰακώβ, ἵνα λάβῃ καὶ τὸν ἄλλον μανδραγόραν. διὰ τοῦτο ἐν τοῖς μανδραγόροις ἐπήκουσε κύριος τῆς Ῥαχήλ.

5. ὅτι καίγε ποθήσασα αὐτοὺς οὐκ ἔφαγεν, ἀλλὰ ἀνέθηκεν αὐτοὺς ἐν οἴκῳ κυρίου, προσενέγκασα ἱερεῖ ὑψίστου τῷ ὄντι ἐν καιρῷ ἐκείνῳ.[47]

1 Then an angel of the Lord appeared to Jacob, saying: Rachel will bear two children, because she despised the company of her husband, and has chosen chastity.

2 And had not Leia my mother paid the two apples for the sake of his company, she would have been able to bare eight sons; for this reason she bore six, and Rachel the two: because by the mandrakes the Lord visited her.

3 For he perceived that for the sake of children she wished to be present with Jacob, and not for love of pleasure.

4 For she continued and the next day also she again gave Jacob, so that she could take the other mandrake. Because of this, by the mandrakes the Lord listened to Rachel.

5 For although she desired them, she did not eat them, but offered them in the house of the Lord, offering them to the one who was priest of the Most High at that time.

Testament of Issachar 2:2 literally states that YHWH visited Rachel ἐν τοῖς μανδραγόροις (“by/in the mandrakes”), and further explains that had Leah not given Rachel the mandrakes, but kept them for herself, she would have borne eight sons rather than six (assuming that the twelve sons of Jacob were inevitable). But because she exchanged two mandrake fruits to Rachel for two evenings with Jacob, Rachel bore two children—with T. Iss. 2:4 explaining that Rachel quite formulaically bore one son for each mandrake fruit.

Testament of Issachar 2:4 explicitly reiterates that it was indeed the mandrakes that caused her sudden fertility: διὰ τοῦτο ἐν τοῖς μανδραγόροις ἐπήκουσε κύριος τῆς Ῥαχήλ (“because of this, by the mandrakes the Lord listened to Rachel”). However, we are not told why or what it is specifically about the mandrakes that prompted YHWH to cause Rachel to become pregnant “because of the mandrakes.”

It is not until verse 5 that an apology is offered that dismisses the problem of the efficacy of the mandrakes as a fertility enhancer. The text argues that Rachel did not ingest the mandrakes or their fruit, but rather offered them to priest as a sacrificial offering to the Most High. In doing so, T. Iss. is able to acknowledge that the mandrakes did, in fact, cause Rachel’s fertility, thereby supporting and perpetuating the canonical presence of the mandrakes, and yet because the text of Gen. 30 does not explicitly state that Rachel consumed the mandrakes, T. Iss. is able to deny Rachel’s participation in the fertility myth by claiming that she offered the mandrakes to the priest instead of consuming them, thus still pregnant “by or because of the mandrakes,” yet crediting her fertility directly to YHWH and not the consumption of the mandrakes, thus portraying Rachel as dependent on YHWH alone. If T. Iss. was composed around 150 BCE as Kee suggests, this would demonstrate that in the mid-2nd C. BCE there was already an attempt in the Jewish literary tradition to absolve Rachel from any involvement with fertility myths, especially those that proved effective.

However, we should not discount the possibility that T. Iss. 2:5 is a later gloss that simply seeks a different apologetic solution to the fertility myth problem of Gen. 30:14–24. The references to the efficacy of the mandrakes in T. Iss. 2:2 and 2:4 are consistent with the references to the efficacy of the mandrakes in Gen. 30:14–24 if we exclude the glossed phrase אֲשֶׁר–נָתַתִּי שִׁפְחָתִי לְאִישִׁי (“because I gave my maid to my husband”) in MT Gen 30:18. It may be the case that the gloss in MT Gen. 30:18 and T. Iss. 2:5 are two different means of achieving the same apologetic goal—removing any reliance on the legendary potency of mandrakes as a fertility enhancer.

The idea to offer up the mandrakes (דוּדָאִים) to the priests as a sacrifice to YHWH may be based on the homonym דּוּדָאֵי (“baskets”) in Jer. 24:1: הִרְאַנִי יְהוָה וְהִנֵּה שְׁנֵי דּוּדָאֵי תְאֵנִים מוּעָדִים לִפְנֵי הֵיכַל יְהוָה (“YHWH showed me, and behold two baskets of figs set before the temple of YHWH”). It could be the case that the Greek author of T. Iss. was far enough removed from Hebrew fluency to confuse the two words—דוּדָאִים and דּוּדָאֵי—to inspire the non-canonical tale of Rachel presenting the דוּדָאִים before the “house of the Lord” (οἴκῳ κυρίου) as he remembered (mistakenly) being done in the prophecy in Jer. 24:1.

It is also possible that the Jer. 24:1 reference to the שְׁנֵי דּוּדָאֵי תְאֵנִים ("two baskets of figs") set before the temple of YHWH was originally not a reference to baskets at all, but to “two mandrake fruits,” with the word traditionally used for “figs,” תְאֵנִים, employed in construct to describe the fruits of what the author understood to be the male plural construct of mandrakes: דּוּדָאֵי. This is especially possible given the fact that LXX Gen. 30:14 expands the HB דוּדָאִים into μῆλα μανδραγόρου (“fruit of the mandrakes”), clearly understanding the fruit of the mandrakes to be separate from the mandrake plant itself, with the fruit being the efficacious element of the plant.

Both Tg. Onq. and Tg. Neof. preserve the gloss “because I gave my maid to my husband” in Gen. 30:18. Targum Pseudo-Jonathan also faithfully preserves the secondary etymology from the Hebrew text, but adds a third etymological interpretation. Because neither of the two etymologies provide the required homophone alliterating Issachar’s name once the Hebrew שְׂכָרִי (“my wage”) was rendered into its Aramaic equivalent, אגרי, Tg. Ps.-J. adds an additional etymology built around the homophonic עסיקין (“to be busy, take pains”), the masculine plural active participle of the root עסק, thereby offering an etymology that alliterates aurally in the Aramaic: “because they will be busy (iss-ee-KEEN) in the Torah, they named him Issachar (יששכר).

We should also make note of the gloss in Tg. Ps.-J. Gen. 30:21 that preserves yet another problematic fertility myth:

Then after this she bore a daughter, and she called her name Dinah, because she said, “It is right from before the Lord that half of the tribes would be from me, but from Rachel, my sister, two tribes would come forth, just as came forth from each of the maidservants.” Then the prayer of Leah was heard from before the Lord, and the fetuses of their wombs were exchanged, and Joseph was given into the womb of Rachel, but Dinah into the womb of Leah.

Targum Pseudo-Jonathan Gen. 30:21 adds a midrash that paints Leah in a favorable light—one in which she prays to God that her sister Rachel might not bear fewer sons than their maidservants. Because of this selfless act, the targum records that the fetuses in each of their wombs were swapped, and Leah—who was to bear Joseph—now bore Dinah, while Rachel now bore Joseph. Of course, Tg. Ps.-J. also presumes the coming birth of Benjamin, something that y. Ber. 1:340 understood as nothing less than evidence that qualified Rachel as a prophet.[48]

Some later interpreters sought to avoid references to mandrakes altogether, thereby removing Leah and Rachel from the participation in the fertility myth. Within the Talmud, b. Sanh. 99b references the דודאים in Gen. 30:14, portraying Rabbi Levi arguing that they are merely violets, and Rabbi Yonatan countering that they are סביסקי (sebisqey), a kind of spice—both of which would be used for fragrance to set a romantic mood and therefore avoid active consumption of the fertility aid and consequent confirmation of the fertility myth.

However, while we see the desire to obscure the efficacy of mandrakes as a fertility enhancer in the textual tradition that gave us the MT, LXX, and the Targums, we also find that there are Jewish interpretative traditions that had no problem with the reference to the mandrakes as the catalyst for pregnancy. Most notably, Rabbi Levi states in Gen. Rab. 72.5, “Come and see how acceptable was the mediation of the mandrakes, for through these mandrakes there arose two great tribes in Israel, Issachar and Zebulon.”[49]

The 13th C. Jewish scholar, Moses ben Nahman (better known as Nachmanides or Ramban) would later confirm the distinction between the fruit of the mandrakes and the plant itself, but disagreed about the efficacious part of the plant with regard to fertility, arguing that the fruit caused the fragrant odor like jasmine and contributed to a romantic and pleasurable atmosphere, while the roots of the plant were believed to aid in fertility:

The correct (interpretation) is that she [Rachel] wanted them [the dudaʾim] for delight and pleasure from their scent (להשתעשע ולהתענג בריחן), for Rachel was visited with children through prayer (בתפלה), not by medicinal methods (לא בדרך הרפואות). And Reuben brought the branches of dudaʾim, or the fruit (או הפרי), which resemble apples and have a good odor. The root (השרש), however which is shaped in the form of the human head and hands (בצורת ראש וידים), he did not bring (לא הביא), and it is the root which people say is an aid to pregnancy. And if the matter be true, it is by some peculiar effect (סגולה), not by its natural quality. But I have not seen it thus in any of the medicinal books discussing them [mandrakes].[50]

Thus, it is possible that the LXX’s addition of the word μῆλα (“fruit”) to its interpretation of the word דוּדָאִים provided a subtle distinction between the fruit and the mandrake plant that later interpreters like Nachmanides used apologetically to distance Rachel from participating in the fertility aspects of the mandrake tradition. However, Nachmanides’s interpretation ignores the fact that the LXX portrays Rachel as keeping the μῆλα μανδραγόρου, the “fruit of the mandrakes,” as the fertility-enhancing substance. This conforms more closely with the explanation offered in the much earlier T. Iss. 2:5, as well as supporting my proposed interpretation in Jer. 24:1.

Nachmanides realized that the myth was untrue, but that it was still mentioned in the text of Gen. 30 as enhancing fertility, so he dubbed it a segulah (סגולה)—a procedure not based on medical or scientific logic, yet believed to be efficacious in improving a situation or protecting a person from harm (e.g., a spiritual charm which acts with no rational explanation or understanding). Thus, as late as the 13th C. CE, there was an acknowledgement that the mandrakes likely played a role in the pregnancies of Leah and Rachel.

Finally, perhaps most notable is Josephus’s retelling of the Genesis 30 narrative. Antiquities 1:307–8 (1.19.8) offers a largely faithful retelling of the episode of the mandrakes, but tellingly does not include the secondary gloss, “because I gave my maid to my husband,” when accounting for the name of Issachar. Only the primary explanation, that he was τὸν ἐκ μισθοῦ γενόμενον (“one born by hire”) remains in Josephus’s explanation:

307 Now Reubel, the eldest son of Lea, brought apples of mandrakes to his mother. When Rachel saw them, she desired that she would give her the apples, for she longed to eat them; but when she refused, and bid her to be content that she had deprived her of the benevolence she ought to have had from her husband, Rachel, in order to mitigate her sister’s anger said she would yield her husband to her; and he should lie with her that evening.

308 She accepted of the favor; and Jacob slept with Lea, by the favor of Rachel. She bare then these sons: Issachar, denoting one born by hire (Ἰσσαχάρης μὲν σημαίνων τὸν ἐκ μισθοῦ γενόμενον); and Zabulon, one born as a pledge of benevolence towards her; and a daughter, Dina.

This may support the theory that there was an alternative tradition of the Gen. 30 text that did not possess the interpolation referencing Leah’s maid, or, that Josephus clearly realized that it was an interpolation, that it made no sense, and simply left it out of his retelling of the text.

Conclusion

Mandrakes have a long and well-documented history in ancient Egyptian art and a wealth of classical Greek and Latin literary compositions as a sought-after medicinal plant that cures any number of ailments, but that is best known as a soporific and a fertility enhancer. The legend of the shrieking mandrake doesn’t actually appear in literary sources until the 12th C. CE, but legends of the lethal dangers of its extraction from the ground date back to the first C. CE.

Mandrakes appear in the Bible on multiple occasions as efficacious both in generating a seductive atmosphere (Song 7:13) and as efficacious in promoting fertility (Gen. 30:14–24). Indeed, the mandrakes are central to the production of what would become the 12 tribes of Israel. Later interpreters recognized the reliance upon the mandrake fertility myth and offered a number of apologetic interpretations to disguise or eliminate it.

The T. Iss. reaffirms the mandrakes’ power to affect fertility. But instead of consuming the דוּדָאִים, T. Iss. states that Rachel offered it to the priests as a sacrifice to YHWH—an interpretation that may have been inspired by the homonymic דּוּדָאֵי תְאֵנִים, traditionally rendered “baskets of figs” in Jer. 24:1, but possibly a reference to “mandrake fruits” presented at the temple of YHWH. Testament of Issachar’s interpretation preserves the mandrake fertility myth while removing Rachel from reliance upon it for pregnancy. While the targums would largely preserve what would become the MT’s interpretative tradition, including the Gen. 30:18 gloss, “because I gave my maid to my husband,” later rabbinic traditions sought to obfuscate the very presence of the mandrake fertility myth by proposing alternative explanations for Rachel and Leah’s pregnancies.

Robert R. Cargill

University of Iowa

[1] “…Not poppy, nor mandragora, Nor all the drowsy syrups of the world, Shall ever medicine thee to that sweet sleep, Which thou owedst yesterday.” Shakespeare, Othello Act 3, Scene 3. “Give me to drink mandragora...That I might sleep out this great gap of time, My Antony is away.” Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra Act 1, Scene 5.

[2] “And shrieks like mandrakes torn out of the earth, That living mortals, hearing them, run mad.” Romeo and Juliet Act 4, Scene 3. “Would curses kill, as doth the mandrake’s groan…” King Henry VI Part II, Act 3, Scene 2.

[3] “Thou whoreson mandrake, thou art fitter to be worn in my cap than to wait at my heels.” King Henry IV Part II, Act I, Scene 2. “He was for all the world like a forked radish, with a head fantastically carved upon it with a knife. He was so forlorn, that his dimensions to any thick sight were invisible; …yet lecherous as a monkey, and the whores called him mandrake.” King Henry IV Part II, Act III, Scene 2. Shakespeare likely refers to mandrakes a seventh time, only not by name, in Macbeth Act 1, Scene 3: “Were such things here as we do speak about? Or have we eaten of the insane root, That takes the reason prisoner?”

[4] For more medieval and modern examples of literary references to mandrakes, see Anthony John Carter, “Myths and Mandrakes,” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 96/3 (2003): 144–47.

[5] The classical authors wrote about this reproductive myth as fact. Hippocrates claims in De Superfoet 18 that “When women with child long for coals, the appearance of these things is to be seen on the child’s head.” Pliny the Elder writes, “a thought suddenly flitting across the mind of either parent is supposed to produce likeness or to cause a combination of features, and the reason why there are more differences in man than in all the other animals is that his swiftness of thought and quickness of mind and variety of mental character impress a great diversity of patterns” (Nat. 7.12 [7.52]). The Talmudic passage b. B. Meṣiʿa 84a tells the shocking story of Rabbi Yochanan, who “would sit before the gates of the ritual bath, he reasoned: ‘When the Jewish women come out from their ritual immersions, let them see me so that their children will turn out as good looking as I am and as learned in Torah as I am.’” See also Gen. Rab. 73:10 and Num. Rab. 9:34. See Havelock Ellis, Studies in the Psychology of Sex, Volume 5 Erotic Symbolism; The Mechanism of Detumescence; The Psychic State in Pregnancy (2d ed.; Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Co., 1912); J. W. Ballantyne, Manual of Antenatal Pathology: The Embryo, (New York: William Wood & Company, 1904); Hermann Heinrich Ploss, and Maximillian Bartels, Das Weib in der Natur- und Völkerkunde: anthropologische Studien, vol. 1 (Leipzig: Th. Grieben, 1897), ch. 31; Iwan Bloch (as Gerhard von Welsenburg), Das Versehen der Frauen in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart und die Anschauungen der Aerzte, Naturforscher und Philosophen darüber (Leipzig: Barsdorf, 1899). For the beginnings of the argument against maternal impression, see James Augustus Blondel, The Strength of Imagination of Pregnant Women Examin’d: And the Opinion that Marks and Deformities in Children arise from thence, Demonstrated to be a Vulgar Error (London: J. Peele, 1727).

[6] For skepticism about 20th C. claims of maternal impression, see A. G. Pohlman, “Maternal Impression,” in Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 1911 (ed. L. J. Rettger; Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, 1912), 65–70.

[7] Ioan P. Couliano, Out of This World: Otherworldly Journeys from Gilgamesh to Albert Einstein (Boston: Shambhala, 1991), 33–49.

[8] Pausanias, Descr. 3.18.1.

[9] See Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve, “Brief Mention,” American Journal of Philology 37 (1916): 505. Cf. J. Rendel Harris, “The Origin of the Cult of Aphrodite,” Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, Oct/Dec 1916.

[10] Christian Rätsch, The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants: Ethnopharmacology and Its Applications (2d ed.; trans. John R. Baker; Rochester, Vermont: Park Street Press, 2005), 353.

[11] Hippocrates, Fist. 11.

[12] Pliny, Nat. 8.41 [8.101].

[13] Pliny, Nat. 14.19 [14.111].

[14] Pliny, Nat. 25.94 [25.147–50].

[15] Dioscorides, Mat. Med. 4-76.

[16] Demosthenes, [4] Philip. 10.6.

[17] Xenophon, Symp. 2.24.

[18] Aristotle, Somn. vig. 3.

[19] Plato, Resp. 6.488c.

[20] Celsus, De Medicina 3.18.12.

[21] Celsus, De Medicina 5.25.2.

[22] Plutarch, Quaest. conv. 3.5.2.

[23] Plutarch, Adol. poet. aud. 1.

[24] Athenaeus, Deipn. 3.97.

[25] Mark D. Merlin, “Archaeological Evidence for the Tradition of Psychoactive Plant Use in the Old World,” Economic Botany 57/3 (2003): 305.

[26] Some have conjectured that two young girls named Meritaten-tasherit and Ankhesenpaaten-tasherit may have been the daughters of Meritaten and Smenkhare. However, this is speculation as the daughters may have been the offspring of Akhenaten and his second wife (after Nefertiti), Kiya, since both daughters only appear in texts that once mentioned Akhenaten’s second wife Kiya. It is also possible that they were fictional. Regardless, the fact that the two speculative offspring were daughters still leaves Smenkhare without a male heir, thereby supporting this interpretation that Meritaten was offering mandrakes to Smenkhare for the purpose of bringing about virility that would result in a male heir.

[27] The King Tutankhamun Exhibit, Grand Egyptian Museum, Giza.

[28] Merlin, “Archaeological Evidence,” 317; Cf. William J. Emboden, “The Sacred Journey in Dynastic Egypt: Shamanistic Trance in the Context of the Narcotic Water Lily and the Mandrake,” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 21/1 (1989): 61–75.

[29] E.g., EA 287, sent by Abdi-Kheba, ruler of Jerusalem, to the king in Egypt begging for military support to defend against attacks from nearby towns.

[30] Theophrastus, Hist. Plant. 9.8.7.

[31] Pliny, Nat. 25.94 [25.148].

[32] Translation by William Whiston (1737). In Ant. 8.45–48, Josephus tells a similar story about King Solomon’s ability to cast out demons, as well as another a man named Eleazar, who used Solomon’s incantations along with “a ring bearing on its seal a root of the sort mentioned by Solomon” (δακρύλιον ἔχοντα ὑπὸ τῇ σφραγῖδι ῥίζαν ἐξ ὧν ὑπέδειξε Σολόμων), which is likely a reference to the root mentioned here.

[33] Josephus may be referring here to a specific variety of mandrake that grew on the eastern shore of the Dead Sea near the village of Baara (Eusebius, Onom. 44.21), which is listed as Baarou on the Madaba Map.

[34] Frazier points out that the first C. CE Greek physician Dioscorides states in Mat. Med. 4-76, “Romans called the fruit mala canina, which betrays the tale of its extinction by a dog,” lending credence to Josephus’s late 1st C. CE story. See Harris, J. Rendel, “The Origin of the Cult of Aphrodite,” Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, Oct/Dec 1916: 361.

[35] A 12th C. CE manuscript in the British Museum, Harl. 4986, recounts the legendary prescriptions of drawing iron circles around the mandrake, tying the dog to it and placing food at a little distance, or devising a mangonel with a trigger that can be activated from some distance. While some distance is described between the harvester and the mandrake, there is still no reference to a shriek produced by the mandrake. See George C. Druce, “The Elephant in Medieval Legend and Art,” Journal of the Royal Archaeological Institute 76 (1919): 46.

[36] See Druce, “Elephant in Medieval Legend,” 42. Druce notes that for Thaun’s translation, the MS. Nero A v. at the British Museum and MS. 249 at Merton College, have been used.

[37] Druce, “Elephant in Medieval Legend,” 43.

[38] Anthony Preus, “Drugs and Psychic States in Theophrastus’ Historia plantarum 9.8–20,” in Theophrastean Studies on Natural Science, Physics and Metaphysics, Ethics, Religion and Rhetoric (ed. William W. Fortenbaugh and Robert W. Sharples; Studies in Classical Humanities 3; New Brunswick and Oxford: Transaction Books, 1988), 79.

[39] We should not discount the possibility that this reference to “my beloved” (דּוֹדִי) at the end of Song 7:13, especially given its placement before the verbצָפַנְתִּי (“I have reserved”) and the absence of a relative clause, may have experienced the elision of an aleph while being rendered into the construct form, and originally read, “…all choice fruits, new as well as old, mandrakes (דּוּדָאֵי) I have reserved for you.” However, given the frequency of the word דּוֹדִי (“my beloved” recurring throughout Song, this is unlikely, especially given the LXX’s preservation of ἀδελφιδέ μου (“my beloved”) in LXX Song 7:14. Nothing in Song is attested in the DSS after 7:9, so they are of no help in reconstruction.

[40] Michael Zohary, Plants of the Bible (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983).

[41] Edward M. Cook, “Why Does Rachel Want the Mandrakes?” Ralph the Sacred River, Dec. 18, 2004, www.ralphriver.blogspot.com/2004/12/why-does-rachel-want-mandrakes.html.

[42] Hermann Gunkel, and Mark E. Biddle, Genesis, (Mercer Library of Biblical Studies; Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 1997), 326.

[43] Note the double etymology for the name of Joseph—the original, rooted on the verb אסף (“to gather”), which verses 23–24 explain, אָסַף אֱלֹהִים אֶת–חֶרְפָּתִי (“God has gathered up/taken away my reproach”), וַתִּקְרָא אֶת–שְׁמוֹ יוֹסֵף (“so she called his name Joseph”), and the second etymology, rooted on the verb יסף (“to add”) which “prophetically” adds, לֵאמֹר יֹסֵף יְהוָה לִי בֵּן אַחֵר (“saying, ‘May YHWH add to me another son’ ”), likely appended to the first after the later Benjamin tradition was added to the Rachel story in Gen. 35:16–18.

[44] The DSS are of little assistance as there is no scroll that contains the mandrake episode from Gen. 30, with the exception of 4Q364 (4QPentateuchal Paraphrases) f4b+ei:8–9, which Tov has reconstructed with only a few letters on a two fragments reading, [וילך ראובן בימי קציר חטי]ם אחר יעקוֹ[ב אביו אל השדה וימצא דודאים בשדה ויבא אותם ]אל לאה א[מו ותואמר רחל אל לאה ת]ני (“[Reuben went out in the days of the wheat harves]t after Jaco[b his father to the field and he found [mandrakes in the field and he brought them] to Leah [his] mo[ther and Rachel said to Leah, ‘Gi[ve me’…]”). See Sidnie White Crawford, “4Q364 & 365: A Preliminary Report,” in The Madrid Qumran Congress: Proceedings of the International Congress on the Dead Sea Scrolls, Madrid 18–21 March, 1991 (eds. Julio Trebolle Barrera and Luis Vegas Montaner; 2 vols; Leiden: Brill, 1992), 1:217–228.

[45] Text from M. De Jonge, et al., The Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs: A Critical Edition of the Greek Text (Pseudepigrapha Veteries Testamenti Graece; Leiden: Brill, 1997).

[46] See pg. 802 of H. C. Kee, “Testament of Issachar,” in Charlesworth, The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, (2 vols.; New York: Doubleday, 1983), 1:775–828.

[47] M. De Jonge, et al., The Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, 80–84.

[48] Y. Ber. 1:340: “Rabbi [said] in the name of the House of Yannai, ‘Originally [as a fetus], Dinah was a male. After Rachel prayed, she was changed into a female. In this regard it says, “Afterwards she bore a daughter, and called her name Dinah” (Gen. 30:21). After Rachel prayed, Dinah was changed into a female.’ And R. Judah b. Pazzi said in the name of the House of R. Yannai, ‘Our mother Rachel was one of the earliest prophetesses. She said, “Another shall descend from me.” In this regard it is written, “She called his name Joseph, saying, ‘May the Lord add to me another son’ (Gen. 30:24)”.’”

[49] Interestingly, Gen. Rab. mentions only Leah’s pregnancy.

[50] Note on Gen. 30:14 from Nachmanides, Commentaries, 369–370. The fact that there is disagreement of whether dudaʾim/ mandragora is the root, leaf, flower, or fruit should not concern us, as in reality all parts of the plant possessed the atropine drug, and therefore would have elicited some effect on the individual ingesting any part of the plant.