How did the Apostles Peter and Paul die?

It feels like we should know the answer to this question, right? Here we have two of the greatest Apostles mentioned in the Bible, so it stands to reason that we should have a few details about how each met their demise. After all, we not only have multiple, incredibly detailed accounts about the death of Jesus, but we possess many other death accounts of far less significant individuals in the New Testament like Judas (for more, see How Did Judas Die?), Herod Agrippa (Acts 12:23), Ananias and Sapphira (Acts 5:1–11), and even Eutychus, who fell asleep and out of a window to his death while Paul was preaching in Acts 20:9. If these less than savory characters have their deaths described in the Bible, then two of the most prominent Apostles should at least have their deaths described in a manner similar to the martyrdom of Stephen in Acts 7, right?

This, however, is not the case. And here we have a great example of how traditions develop over time and eventually become "what is known"—stories we have heard and believe to be true, and often assume are preserved in the Bible somewhere, but actually aren't. The deaths of Peter and Paul are two of these stories. Since you probably have a vague recollection of their deaths that you are trying to sort out, let’s jump to a deceptively simple question that might help.

What does the New Testament say about the deaths of Peter and Paul? Answer? Nothing.

The Book of Acts ends with Paul in Rome alive and preaching unfettered (Acts 28:30–31). In fact, neither Paul nor any of the 12 Apostles' deaths (after Judas) are recorded in the New Testament!

Yet, when people describe the deaths of Peter and Paul, we typically hear a couple of stories:

- Their executions were associated with the year 64 CE when Nero instigated a gruesome persecution of Christians to redirect blame for the Great Fire that destroyed the Circus Maximus.

- Peter was crucified upside down because he felt he was unworthy to be crucified in a manner similar to Jesus.

- Paul was beheaded because Roman citizens could not be crucified.

So, where do these details come from? While only a few early Christian works were included in the New Testament, we continue to find more examples and stories that were in circulation in the first centuries CE. Among the more popular were the Apostolic Acts—collections of stories about individual or groups of Apostles—and few reached the popularity of Peter and Paul. For instance, did you know that we have fifteen different versions of the deaths of Peter and Paul—four of Peter, five of Paul, and six of Peter and Paul together—all written by the 6th century CE? Or did you know that there are over 25 significant references to their deaths singly or collectively in other early Christian literature?[1]

Accounts of Peter

| 1. Martyrdom of the Holy Apostle Peter (Acts of Peter 30–41) | Late 2nd–early 3rd centuries CE |

| 2. Pseudo-Linus, Martyrdom of Blessed Peter the Apostle | Late 4th–5th centuries CE |

| 3. Pseudo-Abdias, Passion of St. Peter | Late 6th century CE |

| 4. History of Shimeon Kepha the Chief of the Apostles | 6th–7th centuries CE |

Accounts of Paul

| 1. Martyrdom of the Holy Apostle Paul in Rome (Acts of Paul 14) | 2nd century CE |

| 2. Pseudo-Linus, Martyrdom of the Blessed Apostle Paul | 5th–6th centuries CE |

| 3. Pseudo-Abdias, Passion of Saint Paul | 6th century CE |

| 4. A History of the Holy Apostle My Lord Paul | 6th–7th centuries CE |

| 5. The Martyrdom of Paul the Apostle and the Discovery of His Severed Head | 5th century CE |

Accounts of Peter & Paul

| 1. Pseudo-Marcellus, Passion of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul | 5th–6th centuries CE |

| 2. Acts of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul | 5th–6th centuries CE |

| 3. Passion of the Apostles Peter and Paul | Late 6th–7th centuries CE |

| 4. Pseudo-Dionysius, Epistle to Timothy on the Death of the Apostles Peter and Paul | Late 6th–7th centuries CE |

| 5. Teaching of Shimeon Kepha in the City of Rome | Late 5th–6th centuries CE |

| 6. Doctrine of the Apostles | 5th–6th centuries CE |

References in Other Christian Literature

| 1 Clement 5:1–7 | 80–130 CE |

| Martyrdom & Ascension of Isaiah 4:2–4 | 100–130 CE |

| Ignatius of Antioch, Epistle to the Ephesians 12:1–2 | 110–125 CE |

| Irenaeus of Lyons, Against the Heresies 3.1.1 | c. 174–189 CE |

| Muratorian Canon 34–39 | c. 3rd–4th century CE |

| Tertullian, Prescription against Heretics 36.2–3 | 203 CE |

| Tertullian, Antidote for the Scorpion’s Sting 15.2–3 | c. 211–212 CE |

| Peter of Alexandria, On Repentance/Canonical Epistle 9 | 306 CE |

| Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors 2.5–6 | 313–316 CE |

| Papias & Dionysius of Corinth (Quoted in Eusebius) Ecclesiastical History 2.25.5–8 | c. 325 CE |

| Origen of Alexandria (Quoted in Eusebius) Ecclesiastical History 3.1 | c. 325 CE |

| John Chrysostom, Against the Opponents of the Monastic Life 1.3 | c. 376 CE |

| John Chrysostom, On the Praises of Saint Paul 4.15 | c. 390 CE |

| John Chrysostom, Homilies on 2 Timothy 10.1–2 | c. 393 CE |

| John Chrysostom, Homilies on Acts 46 | c. 400 CE |

| Jerome, Tractate on the Psalms 96:10 | c. 389–391 CE |

| Jerome, On Illustrious Men 1, 5 | 392–393 CE |

You would think that having so many references and versions available would make our job easier, but when it comes to early Christianities...well, let's just say it becomes as difficult to track as other rapidly spreading phenomena with many "versions" and "variants."

So, how do we sort out all of this material to find an answer? One method is to start with the later, dual traditions and the references in other early Christian literature. This may seem like an odd strategy but focusing on these more general details will end up saving us a great deal of time.

When & Where?

Let’s start with location. Tradition associates their deaths with Nero and 64 CE, so let’s see what we find that supports this tradition. (Keep in mind that this date is before what nearly all scholars consider to be the date of the authorship of the earliest of the gospel accounts, making the exclusion of any mention of their death all the more puzzling.)

In which traditions are Peter & Paul executed on the same day of the same year?

| 1. The Martyrdom of Paul the Apostle and the Discovery of His Severed Head |

| 2. Pseudo-Marcellus, Passion of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul |

| 3. Acts of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul |

| 4. Passion of the Apostles Peter and Paul |

| 5. Pseudo-Dionysius, Epistle to Timothy on the Death of the Apostles Peter and Paul |

| 6. Teaching of Shimeon Kepha in the City of Rome |

| 7. Papias & Dionysius of Corinth (quoted in Eusebius) Ecclesiastical History 3.1 |

| 8. Jerome, Tractate on the Psalms 96:10 |

| 9. Jerome, On Illustrious Men 1, 5 |

In which traditions are Peter & Paul executed on the same day of different years?

| 1. Pseudo-Abdias, Passion of Saint Paul |

| 2. A History of the Holy Apostle My Lord Paul |

In which traditions are Peter & Paul executed at the same place?

| 1. A History of the Holy Apostle My Lord Paul |

| 2. Martyrdom of Paul the Apostle and the Discovery of His Severed Head |

How many remain that don’t specify? 14

Thus, the majority of the dual accounts claim they were executed on the same day of the same year, but that they were executed and buried in different locations. However, all but three of the references don’t say anything about the specific relationship.

You might also have surmised from the answers to second question that we also don’t have agreement about the year 64 CE. More than this, however, the Passion of the Apostles Peter and Paul (from the late 6th-early 7th centuries CE) is clear that they were both executed on June 29, 57 CE.

Who Killed Them & Why?

Maybe we'll have more luck if we shift to the other general questions. Nero was emperor from 54–68 CE, but while the date changes don’t impact the association with Nero, they do impact the implied association with Nero’s persecution of Christians in response to the Great Fire. It turns out, though, that there are reasons to question this story about Nero.

The Roman historian Tacitus, writing roughly 50 years after the events, reports that the Great Fire of Rome began in July of 64 CE in the Circus Maximus and burned for 5 days (Annals 15.44). He adds that people almost immediately blamed Nero for the fire, and Nero blamed a group known as the Christians, some of whom he had thrown to animals and burned alive.

However, it is highly unlikely that Christians would have been a large and distinct enough group yet in Rome in 64 CE to provide a believable scapegoat for Nero. For instance, in his correspondence with the emperor Trajan in 112 CE, Pliny the Younger mentions that he has encountered accusations against a group that he knows nothing about that were called "Christians." Trajan’s reply reveals that he has not heard of this group before, either. This would not be possible for a group that less than 50 years earlier Nero infamously blamed for the Great Fire in Rome.

This is not to say that Christians were not among those blamed by Nero, or that Peter and/or Paul were not killed. It does mean, however, that we would do better to read Tacitus as assigning blame for the fire to a contemporary group better known to his later audience that probably reflects his own view of Christians circa 115 CE, instead of a historical reality that indicts a small, largely unknown group of pacifist messianic sectarian Jews for the fire.

There is one final complication here. While the traditions provide individual stories for Peter and Paul that associate their executions with irrational Roman rulers, what is probably our earliest work to reference Peter and Paul’s executions—1 Clement 5:1–7 (written c. 80–130 CE)—associates both deaths with "unjust jealousy." Similarly, near the end of the 4th century CE, John Chrysostom would argue that Paul’s execution was caused by "those waging war against him" (On the Praises of Saint Paul 4.15).

What this brief excursus has shown is that there is no consensus view on Peter and Paul’s executions. The short answer to our question of, "How did they die?" is: we don’t know. However, that is not a very satisfying ending. So, we will end by highlighting some of the unique details about the various traditions of their individual martyrdoms, answering instead why Peter wanted to be crucified upside down and what happened to Paul’s head.

The Martyrdom Traditions of Peter: Why Upside Down?

Peter’s story was one of redemption after his denials of Jesus. He angered the mad king Agrippa II and another man through his teaching of celibacy to their wives. Some later variations will exaggerate this propagation of celibacy so that it came to include the wives of much of the Roman Senate—something that could understandably frustrate those committed to defending the Roman patriarchy.

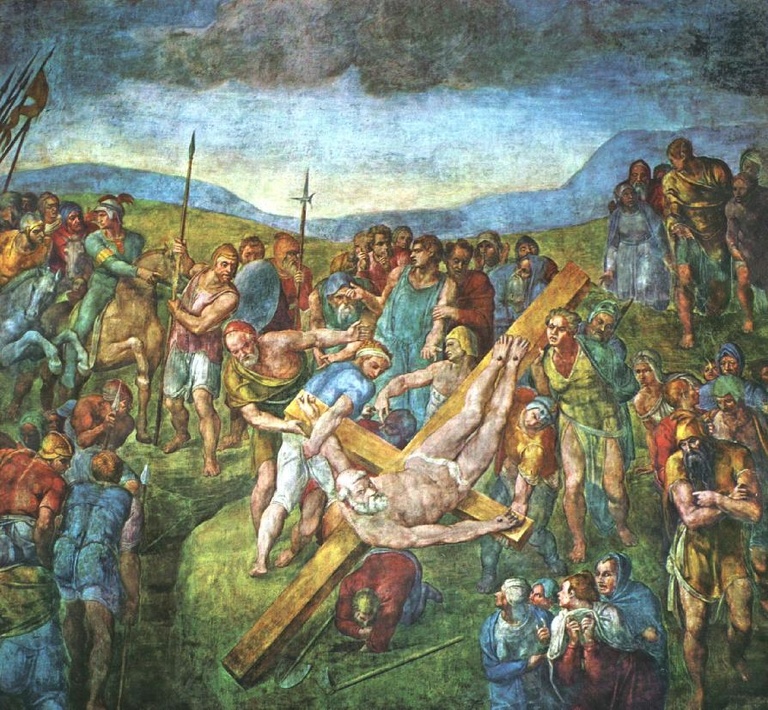

Peter’s followers became aware of a plot to execute him and convinced him to flee, but he encountered Christ as he was leaving. Asking the famous question "Quo Vadis" ("Where are you going?”) and being told that the resurrected Jesus was going to Rome to be crucified again, Peter realized that it was his fate to die in Rome. He returned, was arrested, and requested to be crucified upside down.

So why upside down? The earliest account makes it part of a larger theological point about a world full of Platonic dualism and mysticism—depicting his death actually as a birth. The specific arguments surrounding his crucifixion change considerably among the different versions of the story, but it was not until the 6th century CE History of Shemon Kepha the Chief of the Apostles that the reasoning of the request becomes symbolically kissing the place of Jesus's feet. The main examples of the "humility" tradition are references in Origen and Jerome.

Also, rumors that associated this with the origins of the "Peace Symbol" were wrong. It is more common to see the upside down Petrine cross in horror films and among dark metal bands as a symbol of the antichrist (see What is the Antichrist and is it in the Bible? for more) in the modern world—quite an odd legacy if you think about it.

The Martyrdom Traditions of Paul: What Happened to His Head?

Paul’s account bears a strong resemblance to the story of Eutychus in Acts 20. A servant, perhaps cupbearer, of Nero fell asleep in a window listening to Paul and fell to his death. After he was raised from the dead by Paul, the resurrected servant upset Nero by acknowledging Jesus as the "eternal king," leading Nero to discover that many others among his own bodyguard were Christians. As with Peter, details change in the later retellings. Paul is sometimes guilty of converting Nero’s mistress or concubine in certain versions of the tale, and having converted almost the entire palace in others. Nero had the Christians arrested and Paul beheaded. (Interestingly, a postmortem visit from Paul convinced Nero to release the other Christians!)

The most unique detail to appear in several of Paul’s traditions is that his head got lost. Though the amount of time it was lost as well as the reasons for its rediscovery vary, it was eventually discovered and miraculously rejoined Paul's body.

Conclusion

Understandably, much press these days goes to the search for the "historical Jesus," but in many ways we know less about the great Peter and Paul. Jesus's death, for example, is recorded four times in the New Testament, while Paul and the 12 remaining Apostles (after Judas Iscariot) have none of their deaths recorded. With all the material and traditions available, the absence of the death narratives of the Apostles from all of the canonical lists seems to have been a conscious decision. Perhaps the idea was to focus only on their lives. Maybe it is because by the time the gospels were written, the Apostles had dispersed and the stories of their deaths were unknown. Or, maybe the anonymous gospel authors simply didn’t think that any of the death traditions could be trusted, and excluded them for this reason.

But the continued existence of the martyrdom traditions of the Apostles almost two millennia later is only further evidence that there is often a huge difference between what believers think should be the case and what is actually described in the Bible. For we cannot blame Christians for expecting the deaths of Peter and Paul to be described in the Bible, especially when there are so many similar post-biblical legends and accounts that sound like they fit the narrative, or that believers would really like to be true.

[1] David Eastman (Translations & Introductions). The Ancient Martyrdom Accounts of Peter and Paul. (SBL Writings from the Greco-Roman World 39. SBL Press: Atlanta, 2015). He includes translations of all the accounts and references here, along with several more references and admits his list is probably not exhaustive.