Rome definitely earned its reputation as both violent and hyper-masculine. Our modern word virtue comes from the Latin virtus, which literally means "manly." It was manly to be brave and victorious, dominating your opponents and inflicting your will upon others. Conversely, it was considered "feminine" to be defeated, submissive, and humiliated. One particularly graphic example of Roman art depicted victory as the Roman emperor Claudius killing the female "Britain." Claudius's invasion of Britannia in 43 CE was considered his signature conquest.

Another famous example are the "Judea Capta" coins issued after the Roman suppression of the Jewish Great Revolt. They depict "IVDEA" as a woman seated against a tree on the reverse of the coin mourning in defeat.

In such a society, where women were expected to remain in the home and maintain their dominion there, could women ever be accepted as anything that would be considered tough or fierce? Could they ever be considered, for instance, gladiators?

The answer, remarkably, is YES!

One point to keep in mind is that gladiators were actually a fringe group, and when dealing with fringe groups, there was some blurring of the typically rigid social lines. Even male gladiators were often slaves that could, on rare occasion, become as popular and wealthy as senators or even the emperor himself.

Further, since virtus or "manliness" is a concept or social construct, it does not have to correlate directly to biological sex. There were small windows in antiquity available for breaking boundaries and for non-men to embody those ideals.

Women of Virtue

The tragic story of Lucretia provided a particularly poignant example of how taking ones own life could be seen as a virtuous act. Lucretia, a devout wife, was raped by a prince of Rome (Sextus Tarquinius), who threatened her with false tales of her sexual impropriety in an effort to cover up his assault. While her husband and others believed Lucretia, she took her own life as a way of maintaining her reputation and wresting control over her life back from the assailant, who had turned her into a victim. Her death precipitated a rebellion against the royal house, ending the Roman monarchy and leading to the establishment of the Roman Republic in 509 BCE.

Similarly, the Jewish philosophical work 4 Maccabees takes the form of a praise of the Maccabean martyrs whose stories are told in 2 Maccabees 6–7. The larger goal of this work is to depict Judaism as the ideal of Hellenism, where reason controls the emotions. The elderly father Eleazar, the mother, and their seven sons all choose obedience and an afterlife reward despite the pains of torture and death. The mother’s death in particular is praised:

"How great and how many torments the mother then suffered as her sons were tortured on the wheel and with the hot irons! But devout reason, giving her heart a man’s courage in the very midst of her emotions, strengthened her to disregard, for the time, her parental love…

O mother of the nation, vindicator of the law and champion of religion, who carried away the prize of the contest in your heart! O more noble than males in steadfastness, and more courageous than men in endurance! Just as Noah’s ark, carrying the world in the universal flood, stoutly endured the waves, so you, O guardian of the law, overwhelmed from every side by the flood of your emotions and the violent winds, the torture of your sons, endured nobly and withstood the wintry storms that assail religion." — 4 Maccabees 15:22–23, 29–32

This text praises the woman martyr while reminding us of the secondary status of women. On the one hand, she is lauded as one of the greatest examples of faith—on par with Abraham and Noah—but on the other hand her praise is noteworthy because she had to overcome what were believed to be her natural feminine limitations. Still, she is lauded as a champion despite her execution, displaying the ability to endure physical pain because her reason reminded her of the rewards to come.

One narrative that touches on these connections between gladiators and execution is the Passion of Perpetua and Felicitas. Arrested and executed with other Christians in Carthage around 200 CE, she records her experiences, and even her dreams, while she is in prison. While edited by a later hand, these are believed to represent her own writing and experiences. In her final dream just before she was to be executed, she is transformed into a man and wrestles against an Egyptian, and her victory is rewarded with immortality by God. She awakened and immediately interpreted the dream as representing her coming "victory" in the arena. Perpetua even proves to be "manly" in her death, having to guide the nervous gladiator's sword to her neck to embrace her victorious death.

The Gladiatrix

Since women were executed during public games, it should not be too surprising, then, to learn that some women ultimately competed as gladiators in later games—and that many saw this as a scandal. The grave of Hostilianus, a 2nd century CE magistrate of Ostia, claims he was the first since the city’s founding to have female gladiator competitions. In Ephesus, the graveyard next to the amphitheater contains the graves of both male and female gladiators. Tacitus even claimed that Nero forced noble women to fight in the arena and had female gladiators fighting "under the torches," meaning the main event at night (Annals 15.32).

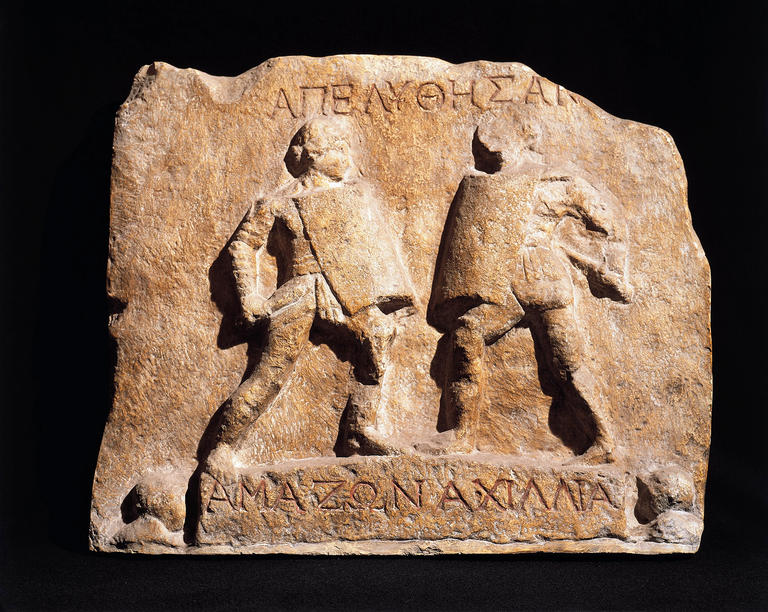

The most intriguing evidence comes from a relief dated to the 2nd century CE in Halicarnassus in Asia Minor. It has a relief of two female gladiators competing. Both are holding shields and daggers and the two are facing one another. One is named "Amazon," after the legendary female warriors. When Pompey returned victorious from the Third Mithridatic War (66–63 BCE), he brought many female warriors that he called "Amazon queens." The other female gladiator is named "Achillia," a feminine form of Achilles, the legendary warrior.

Of course, there were many who hated this practice and saw it as a threat to Roman order. Juvenal explained his hatred of female gladiators because they behaved as men, running away from their gender and showing no modesty (The Satires 6.82 ff). The Roman senate passed laws against middle- and upper-class women competing as gladiators in 11 and 19 CE. Septimus Severus would have to pass laws against the same thing again in 200 CE. Ironically, the vehement objections to the practice in literature and the need to pass multiple laws against it provide some of the best evidence for both the existence of the gladiatrix, or female gladiator, and their enduring popularity.